Background

The Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) has announced that ₦100 billion recovered from corruption cases has been invested in Nigeria’s student-loan and consumer-credit schemes.

According to the EFCC, the funds were drawn from part of the ₦566.3 billion recovered by the agency over the past two years, alongside foreign currencies and more than 1,500 real-estate assets.

The decision to channel a portion of the recovered funds into social-investment initiatives marks a shift toward ensuring that proceeds of corruption are reinvested directly into programmes that benefit the public, rather than being left idle in government accounts.

What the Investment Covers

The EFCC explained that part of the ₦100 billion has been allocated to the Nigerian Education Loan Fund (NELFUND), the federal student-loan scheme aimed at expanding access to higher education.

The remaining portion was invested in a consumer-credit initiative designed to improve financial access for civil servants and low-income earners.

The EFCC chairman clarified that the funds are not donations from the agency but recovered assets remitted to the federal treasury and subsequently appropriated by the government to support the two schemes. This move, he said, demonstrates how anti-corruption recoveries can serve a direct social and economic purpose.

Significance and Potential Benefits

1. Symbolic Value

Redirecting recovered funds into education and credit schemes sends a clear message that anti-corruption efforts can yield tangible social dividends. It transforms recovered assets from symbols of loss into instruments of national development.

2. Support for Students

Nigeria’s tertiary-education costs have risen sharply in recent years, making access to loans critical for students from low-income backgrounds. By strengthening NELFUND, the EFCC’s intervention helps more students finance their education and complete their studies.

3. Credit Access for Workers

The consumer-credit scheme aims to ease financial pressure on workers by providing affordable credit. This not only improves household welfare but can also reduce susceptibility to corruption driven by financial hardship.

4. Institutional Accountability

By linking asset recovery with social-investment programmes, the EFCC reinforces the principle that anti-corruption work should have a measurable impact on citizens’ lives.

Caveats and Areas to Watch

Transparency and Disbursement:

While the ₦100 billion figure is significant, it remains essential to monitor how the funds are disbursed, who benefits, and under what terms. Detailed reporting and independent oversight will be key to maintaining credibility.

Risk of Diversion or Misuse:

Student-loan and credit schemes are inherently vulnerable to mismanagement. Proper auditing and accountability mechanisms must be in place to prevent new leakages or irregularities.

Sustainability:

Relying on recovered funds alone is not sustainable in the long run. The ultimate goal should be to prevent corruption at its roots while integrating recovered funds into a consistent and transparent national budget framework.

Public Awareness:

Many eligible students and citizens remain unaware of the loan and credit schemes. Without effective sensitisation and support structures, the funds might not reach those who need them most.

Broader Context

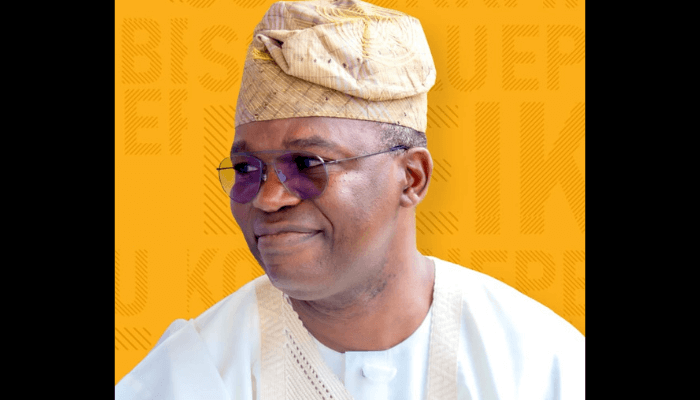

Under the leadership of Ola Olukoyede, appointed EFCC chairman in 2023, the commission has emphasised not only prosecution but also prevention, institutional reform, and asset recovery.

The ₦566 billion recovered over two years represents one of the largest totals in the agency’s history. Investing a portion of that amount into student-loan and credit initiatives aligns with the federal government’s “Renewed Hope” agenda, which prioritises youth empowerment, education, and inclusive growth.

Conclusion

The EFCC’s decision to invest ₦100 billion of recovered corruption proceeds in the student-loan and consumer-credit schemes marks an important turning point in Nigeria’s anti-corruption narrative. It demonstrates how recovered funds can be transformed from mere statistics into meaningful social investments that empower citizens and strengthen trust in public institutions.

However, the true measure of success will lie in how transparently the funds are managed, how effectively they reach intended beneficiaries, and whether they genuinely improve access to education and credit. Fighting corruption, in this sense, is not just about seizing stolen assets—it is about redeploying them for the public good and ensuring that justice yields tangible benefits for ordinary Nigerians.